Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

Feature / Director's column vol.2

Advancing the “frontline” of art at Echigo-Tsumari

Fram Kitagawa ("Art from the Land" editor-in-chef / ETAT General Director)

One of the reasons for why Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale draws attention globally is its capacity to attract participation by internationally acclaimed artists from around the world to produced their art. What brings them to this unprecedented and challenging frontline? We will unravel the reasons from looking at the history of where art is presented, that is, the place or art.

Edit by Uchida Shinichi, Tomoyuki Miyahara (CINRA.NET editorial team), Photo by Nozomu Toyoshima

01 November 2019

The history of the place of art: temples and shrines, castles, and art museums

I would like to talk about art and places where you experience art.

If you look back over history, art was originally created for the walls and altars of religious facilities such as temples and shrines, which gradually reduced in size as they transformed into artworks. Another stream of its history are tableaux (1), which are ornamental scenes from buildings owned by royalty and aristocrats, such as the Palace of Versailles.

(1) Paintings on wooden boards or canvas. While murals are closely related to walls and buildings as well as acts of worship, portable tableaus are considered to be undefined by place-specificity nor purpose.

As many societies transformed into democracies through people’s revolutions, artworks were presented in galleries and art museums, accessible for many people to visit and enjoy. Now, we can experience diverse art forms from paintings and sculptures to photos, movies, installations and performances in all different kinds of facilities.

The history of art criticism, in principle, has evolved as critics were exposed to artworks in those places. Moreover, in the globalised economy, art critics have strengthened their influence in art auctions and art fairs. The media sometimes report that “a famous collector made a successful bid for the most-talked about artwork at a record price.” This, in a sense, the easy-to-understand “peak” of art which would draw attention again if such artworks are presented at an art museum.

“Powerless Structures, Fig.429” by Elmgreen and Dragset (2012, photo by Osamu Nakamura)

Light and shadow reaslised in the ideal “homogenous space”

We could say that the interiors of art museums and galleries are perfected homogenous spaces. This was an ideal of the 20th century. In an exhibition space in the shape of a “white cube” (2), an artwork is perceived to be the same whether it is in Tokyo, New York and Johannesburg and valued the same. Arts had found a collective neutral space where they would be judged regardless of the context such as local culture and history of the place they are presented.

(2) The “white cube” was introduced by MoMA in New York when it was opened in 1929 and since then it is used as a typical description of an ideal exhibition space.

From a broader perspective, the concept of “Universal Space” was proposed by the architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The 20th Century was also the time when that concept was widely spread – a universal and convenient space which could become a restaurant or living space as long as an air-conditioning is installed. This is still a commonly shared conception of space in contemporary society.

However, the distinctive dimensions of culture and life are dismissed with this concept. While the postmodern movement from around 1980 emerged as a critical perspective, I think it wasn’t pervasive enough to replace this “Universal Space”.

On the other hand, there are architects like Hiroshi Hara who designed Kyoto station and Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, KINARE (3) who started their career with a critical perspective towards Universal Space. “Daikanyama Hillside Terrace” designed by Fumihiko Maki takes over the Universal Space in some senses while attempts to engage with community making use of the distinctive character of the place. Art Front Gallery, which I am a representative of, was invited to occupy the space here to explore the possibility of how to utilise this facility.

(3) Launched as “Echigo-Tsumari Koryukan Kinare” in 2003 and re-opened as Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, KINARE in 2012. It is based upon a distinctive concentric structure with a square in the centre with water inside.

I regard the spread of the Universal Space as having brought a larger issue than convenience or comfort. While it may appear democratic and fair at first glance, does it cause friction with our sensibility? Looked at from a longer term point of view, isn’t the present situation only possible in the big cities? I have been thinking along these lines and this deeply relates to how I regard art in Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale.

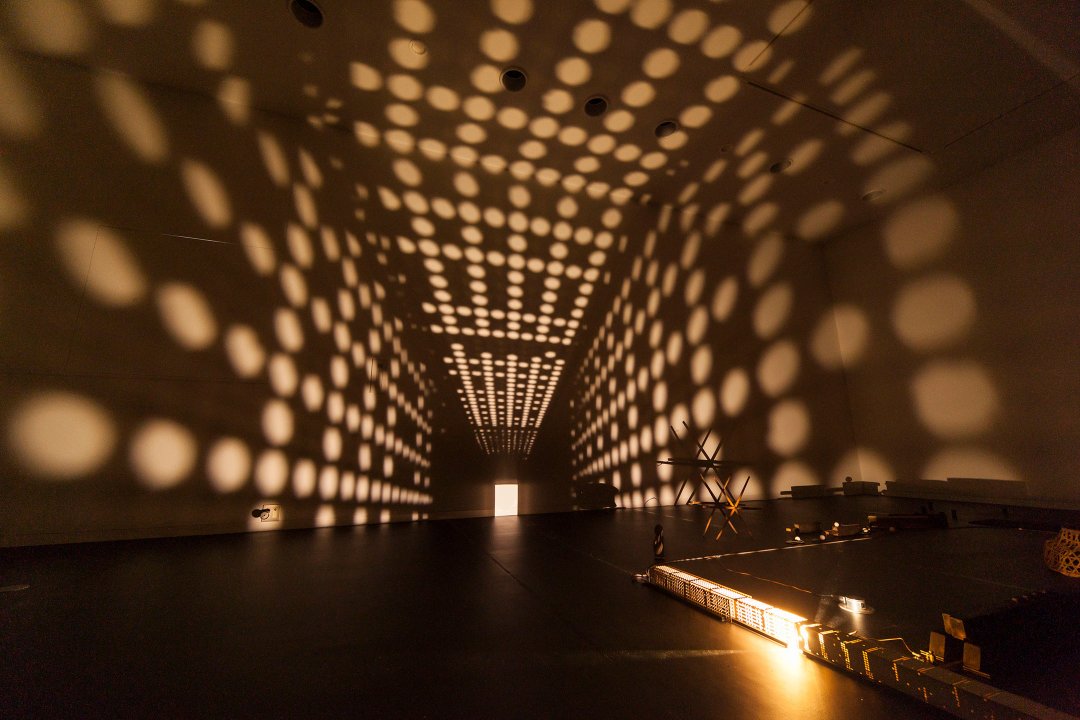

“Palimpsest: Pond of Sky” by Leandro Elrich (photo by Keizo Kioku)

Art moving into a living society

Seeing art in a space like a white cube could provide experiencing highly abstracted or purified artwork or help elaborate criticism. However, is that everything? Artists who sought to bring art out of the museum and connect it closer to daily life made movements in the 1950s and 60s.

Andy Warhol, known for pop art, also worked on producing a rock band and film productions and said that art was not that important in a contemporary society filled with images. This could be regarded as represent the thinking above.

Joseph Beuys said that the conventional art is meaningless for politics but he left the famous slogan “everyone is an artist”. He was an artist who considered the prospect of human beings “engraving the society” for their future.

There have been many other movements (4) but my challenge for the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale from the perspective of attitudes towards the art began with these issues in mind. Bringing artworks to art museums in large cities as they were then was not an option to consider. Rather I wanted to explore spaces other than Universal Space through artworks which eventually lead to opening up the future of the Echigo-Tsumari region.

(4) Since the 1960s, Land Art artworks using natural materials displayed outdoors, and Public Art works installed in public spaces such as squares were developed. Other movements include Art Activism where art engage with social issues through participation and dialogues as well as Socially-Engaged-Art.

I was so pleased that artists from around the world responded positively to such an attempt. The reason why extremely prominent artists such as Christian Boltanski, Antony Gormley, and the late Vito Acconci decided to participate in Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale must have been largely because they were keen to see how this place would transform. The rumour spread that “Echigo-Tsumari is trying something interesting” which resulted in welcoming a more diverse range of artists.

“Les Linges” (2000) by Christian Boltanski (photo by ANZAI)

Illuminating the world from Echigo-Tsumari

Artists attracted to Echigo-Tsumari are also those who try to seek an alternative definition of the richness of space other than Universal Space. Christian Boltanski (5), who has been participating in ETAT since the first iteration, was revolutionary as he injected multi-layered “time” into an abstract exhibition space by bringing in old biscuit tins and taken off clothes. Having a Jewish father, his creation is largely influenced by his conscious attention to the Holocaust issue of the World War II whereas he has created artworks making the best use of the field and closed schools in Echigo-Tsumari that are unique to this place and yet entails the universality.

(5) Christian Boltanski was born in 1944 in Paris. At ETAT, he has presented “Les Linges”, hanging white clothes contributed by locals over the field (2000) and “The Last Class”, a large-scale installation in the closed school (2006, co-production with Jean Kalman).

Leandro Erlich (6), another artist who has deeply engaged with Echigo-Tsumari, takes a similar position.(*6)While his artworks using mirrors and other tricks are often described as illusionistic, I do believe he poses questions on Universal Space. Although he didn’t study architecture himself, he was naturally interested in architecture and grasped there is not such thing as universal space, having architects around such as his father, brothers and aunt. As he attempts to embrace space as something ambiguous rather than homogenizing it, he chose to “reproduce, transfer, and reflect the world”. This is how I interpret his works and it helps us unveil his critical perspective on society.

(6) Leandro Elrich was born in 1973 in Buenos Aires. For ETAT he has presented “Tunnel” (2012), an artwork which tricks on viewers perception, taking an inspiration from distinctive landscape of the region as well as “Palimpsest: Pond of Sky” (2018) which drastically transformed the ordinary scene of Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, KINARE.

For this issue I presented my view by drawing a broad sketch of art and related movements. For me, Echigo-Tsumari stands at the frontline of art. We all live in a reality that is filled with contradictions and conflicts – for instance, disparities widen in the shadow of the advance of globalisation of economy. I wouldn’t say that art has the solution to such problems. However, it may have the possibility to offer clues to resolve things. ETAT exists for exploring such possibilities.

By inviting artists from various regions both within and outside of Japan and embracing ikebana and ceramics in addition to contemporary art was because I have hope for diverse perspectives to contribute to the festival. Echigo-Tsumari is a place where people have lived for 1500 years. The depth of matière (the effect of materials and their quality of works) that are distinctive to this place is abundant and has no comparison to others. At the end of history, when the place for art changes, I would like to be standing at the very frontline of art, on and beside Echigo-Tsumari

Profile

Fram Kitagawa

"Art from the Land" editor-in-chef / ETAT General Director

Art director, born in 1946 in Takada-city (current Joetsu-city) in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. He has been General Director of Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale prior to its launch in 2000. He is the editor-in-chief of this web magazine, “Art from the Land”.