Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

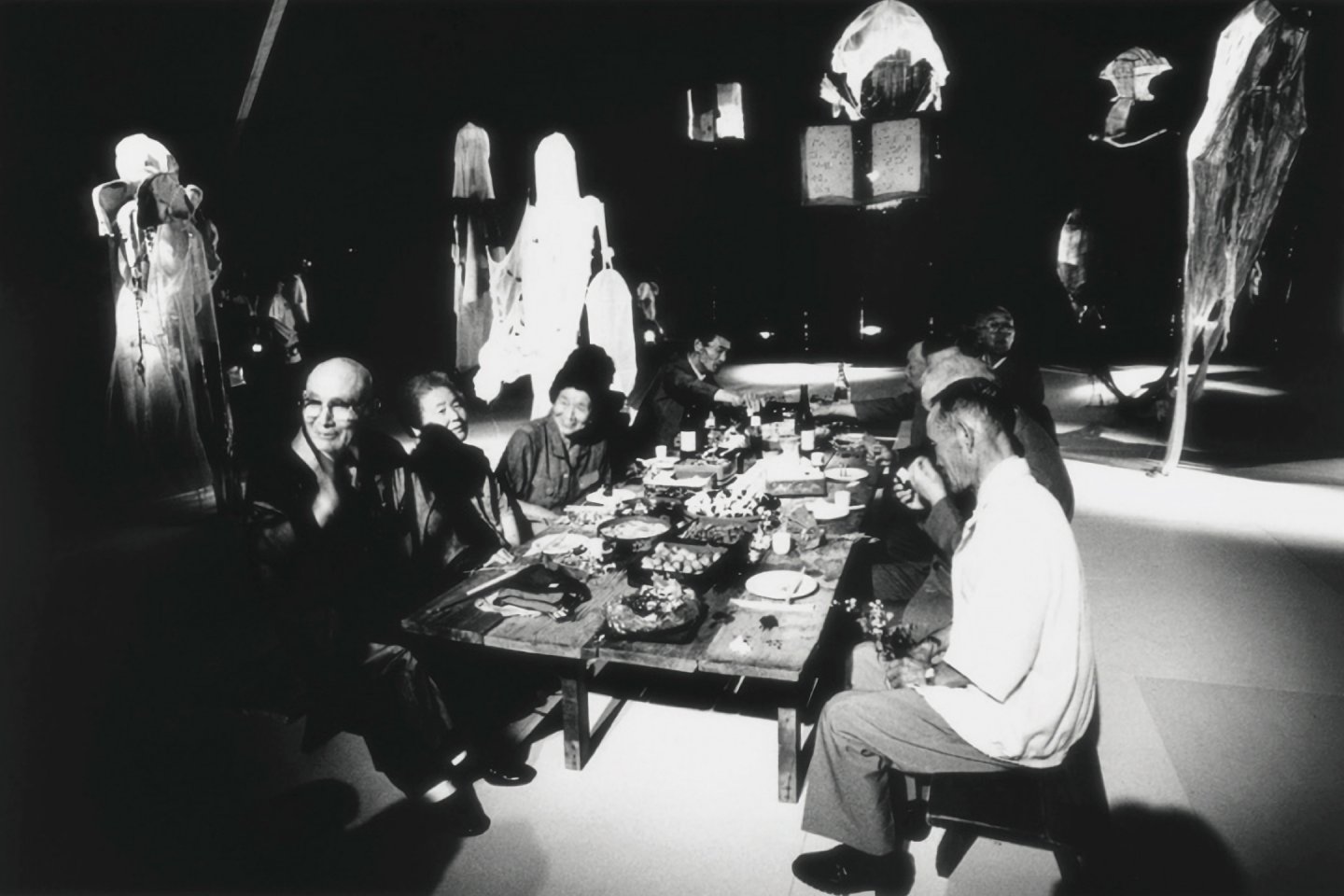

Artwork / Brook Andrew

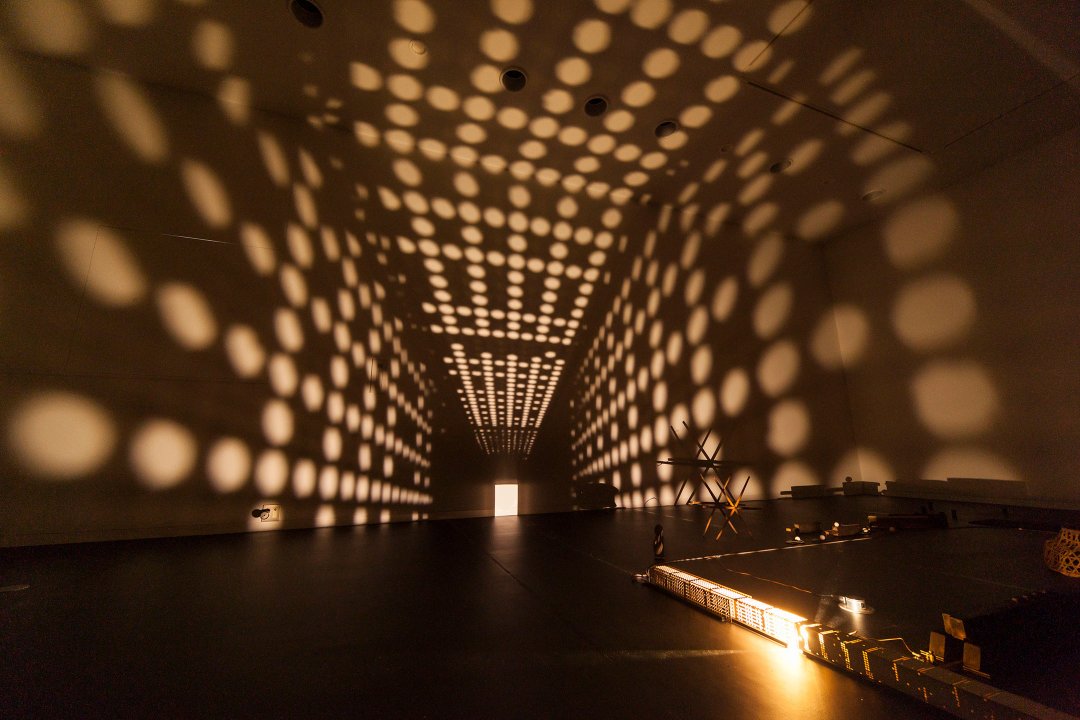

Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang

"Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang" (2012) by Brook Andrew. Photo by NAKAMURA Osamu

Artwork / Brook Andrew

Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang

"Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang" (2012) by Brook Andrew. Photo by NAKAMURA Osamu

“Many edges create a huge network” – eight years on since the establishment of Australia House, Brook Andrew, the Artistic Director of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney in 2020 talked to us.

Text and edit by Art Front Gallery Co., Ltd.

01 December 2020

The “Autumn Gathering at Australia House” was held on 1 November 2020 and local residents of the Urada village, kohebi members and staff members of the NPO came together to prepare for winter and talk about the future of Australia House. Prior to the event, we arranged an online interview with Brook Andrew, the creator of the 2012 artwork “Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang”for Australia House, about his experience in Echigo-Tsumari, as well as his role as Artistic Director for the 22ndBiennale of Sydney.

――What is the current situation in regard to the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia?

We had zero cases today in Melbourne (as of 26 October 2020). The case numbers have been really low and the maximum cases per day we got to was about 700. The number of cases is relatively low.

――Receiving visitors from outside of the region in Echigo-Tsumari was difficult until June 2020 but since that time, we have gradually re-opened to the public and Australia House has started to take booking as an accommodation this autumn.

Wonderful. I would love to return one day.

――How do you describe your experience of Australia House?

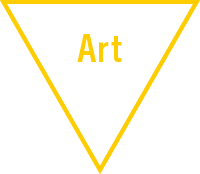

I have a very fond memory of working with local people in the village, the architect of Australia House Andrew Burns, and the entire Echigo-Tsumari team. It was quite an extraordinary experience to work in the community to create the artwork – the community which was incredibly dedicated to look after not only the land and the site but also to keep the cultural connection happening locally and internationally. Australia House is a beautiful building and I was so excited to be with the artist Andrew Rewald and the curator Ulanda Blair when the Australia House was completed in 2012. It was very humbling to meet, work and be with local people, especially in regard to gathering local food growing in the mountain which was then cooked by Andrew Rewald (as part of our project). There were so many fond memories and I can’t believe that eight years have already passed since then.

Profile

Brook Andrew

Born in 1970 in Sydney, Australia, Brook Andrew is a contemporary artist of the Wiradjuri Nation with Celtic ancestry. He has exhibited artworks both nationally and internationally since 1996 and was the artistic director of the 22ndBiennale of Sydney held in 2020. He participated in Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in 2012 and created a permanent artwork for Australia House called Mountain Home – dhirrayn ngurang.

【Photo by Jessica Neath】

“Australia House” by Andrew Burns Architect / Photo by NAKAMURA Osamu

Local villagers, kohebi-members and local supporters working together in preparation for snowfall in winter in order to protect the building. (November 2020).

――It has been eight years since Australia House was built. During these years, many artists, designers and performing artists such as Snuff Puppets have stayed at Australia House and spent wonderful times with your artwork. We would like to ask you about the Biennale of Sydney (1) (“Biennale”) for which you have been engaged as the artistic director. You were the first Indigenous artistic director in the history of the Biennale.

Gerald McMaster co-directed the 18thBiennale in 2012. As a First Nations person from Canada, strictly speaking he is the first Indigenous artistic director. I am the first Australian Indigenous artistic director – which I would say, was very much overdue. This Biennale often has a European focus even though we are in the Asia Pacific region. It was therefore incredibly exciting when Kataoka Mami was appointed as the artistic director for the previous Biennale in 2018.

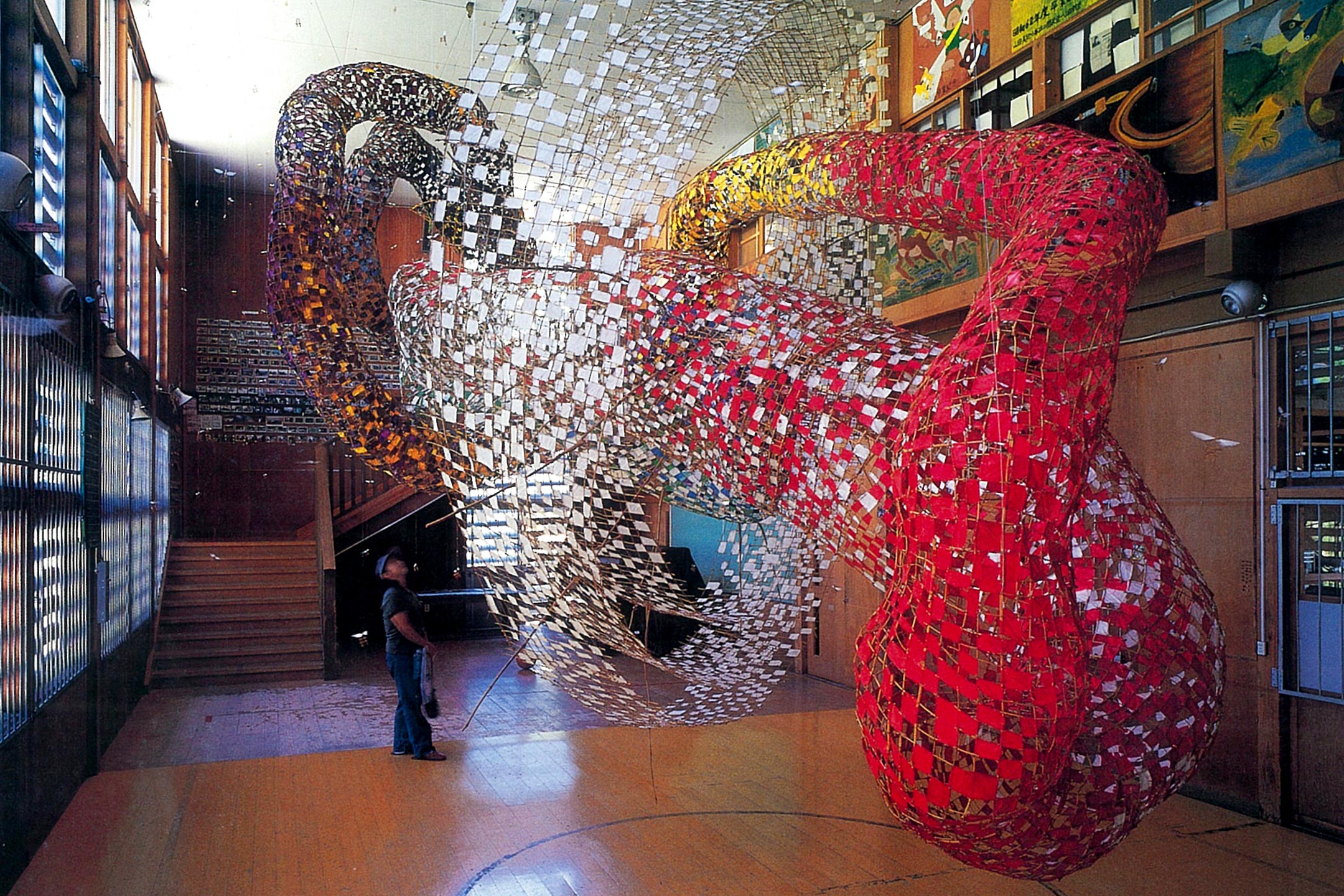

The Biennale 2020 was an important opportunity to embed Indigenous philosophy and protocols within the actual organisation of the Biennale. We held a traditional Indigenous smoking ceremony for the opening of the Biennale and people from different parts of the world were brought together. Mayunkiki, an Ainu person from Hokkaido, was one of the participating artists and I believe meeting with artists and local people in Australia was very important for her own network and her own cultural identity – to be in a place where many other First Nations people exchanged views on issues around, for example, restitution and the environment. There was a strong sense of community which was very much appreciated.

Mayunkiki is a member of the female musical group, MAREWREW and facilitator of Ainu culture presenting the history and culture of tattooing, which was banned by the Japanese government.

Mayunkiki with photography by Hiroshi Ikeda, SINUYE: Tattoos for Ainu Women, 2020. Installation view for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from Open Society Foundations, and assistance from NIRIN 500 patrons. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Zan Wimberley.

*1. A festival of contemporary art held once every two years in Australia. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the 22ndBiennale of Sydney went online in collaboration with Google Arts & Culture.

――The title of the Biennale “NIRIN” means “edge” in a word of your mother’s Nation, the Wiradjuri people of western New South Wales. Tell us about the reason why you chose this word?。

Like Australia, there are many countries and regions which were colonised in the past. Given this history, many art galleries are established from a European and/or North American perspective. While it is rather complex, I wanted to look at various issues with awareness of this dominating perspective, such as the environment, healing, or working together and think beyond its parameters. For example, participants in the Biennale were not limited to artists. Kylie Kwong for instance is a well-known chef in Australia who organises events through her strong connections with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. When I think about things that connect us, “edges” occurred to my mind. We all have edges. When we put these many edges together, they create a huge network. “NIRIN” is a word of my mother’s Nation, the Wiradjuri people of western New South Wales, and it was this word that gave inspiration to artists, creative people and their communities while connecting them together. We ran projects led by artists and communities under this philosophy. It was also a challenge to various forms of co-operation and bureaucratic structures. However, the people working for the Biennale were very supportive and the exhibition turned out to be exciting one.

A much-discussed work of the Biennale of Sydney 2020 – a large-scale installation by Ibrahim Mahana

Ibrahim Mahama, No Friend but the Mountains 2012-2020, 2020. Cockatoo Island.

Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from Anonymous, and assistance from White Cube. Courtesy the artist; Apalazzo Gallery, Brescia and White Cube, London / Hong Kong. Photograph: Zan Wimberley.

――Over 100 groups of artists from around the globe participated in the Biennale. It must have been a hard job. How did you find your experience of being a curator and also artist yourself at the same time?

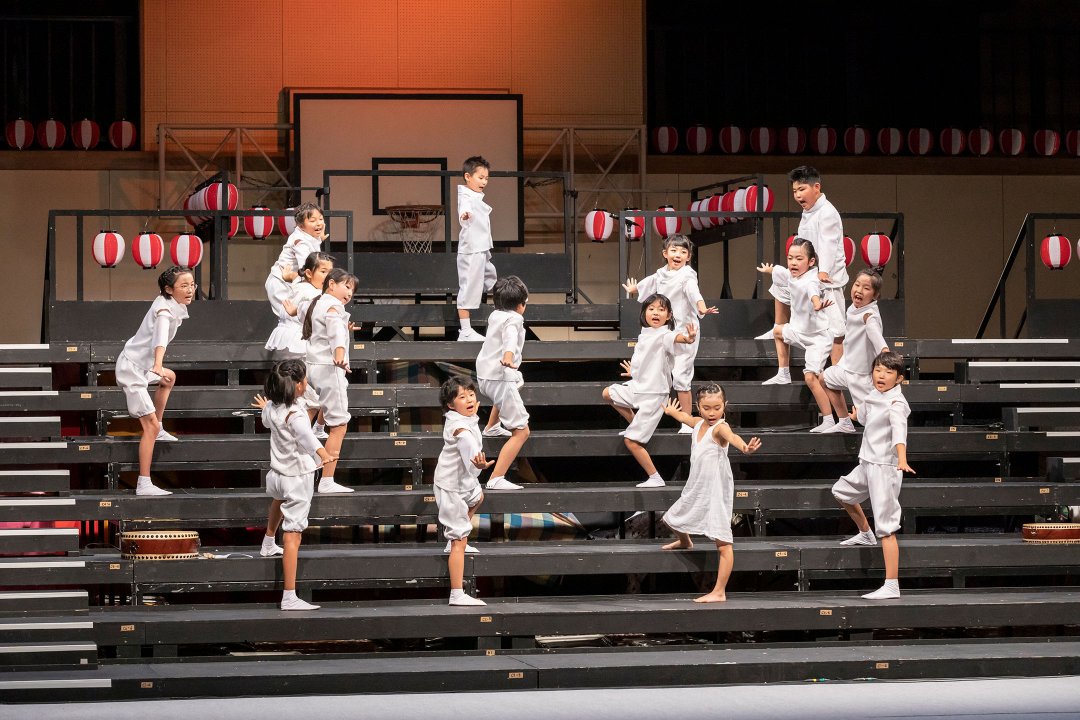

While the number of artists and collectives is 101, the actual number must be at least 250 if we count all the different people involved or even more with the communities involved in making the art exhibitions happen.

I don’t call myself a curator as I find curation has a sort of limiting narrative and process. What is brilliant about being an artistic director is to be able to paint a picture with truly diverse media to create my own palette. When I was offered the director’s position, the first thing I thought of was how I could empower the artists. I do understand the stress, happiness and complexities of participating in art festivals such as biennales and trienniales. I understand sometimes the process is difficult. I wanted it to not be about my ideas or philosophies – it was more about how to create a structure that is inspired by the artistic process which is flexible.

The way artists work is process-driven – one thing leads to another thing and then another thing and even another idea and we follow that trail. I think it is very important to be very open-minded about this process. I can understand that some bureaucracies or arts organisations are often constrained by deadlines which restrict artists. That was why it was important to set up first for this Biennale an artist-led and Indigenous-led philosophy which allowed artists to fulfill their own practice in the way they would like it to happen. While we had to set dates such as the opening and closing dates we made it clear to allow flexibility and it was helpful when the duration of the Biennale was extended for three to four months due to the pandemic. Such flexibility allowed many artists to realise their projects.

Andrew Rewald ran a project in the garden in ETAT2012.

Andrew Rewald, Alchemy Garden, 2019-20. Installation view for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), National Art School. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous assistance from Create NSW. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Zan Wimberley.

――The Biennale of Sydney went online and realised “a virtual biennale”.

It was fortunate that we were able to open the exhibitions to the public. We were able to welcome many people as we ran an international forum inviting First Nations peoples from all around the world. In fact we were quite overwhelmed by the presence of everybody who managed to come to the Biennale in person. If there was anything the pandemic did create, it was the energy to document everything. We created an online experience to be able to see all the works as if you were walking through the venues. We also broadcasted artists’ talks and discussions on YouTube. Although it was only Australians who were able to come and see the Biennale after its re-opening, it is wonderful that we managed to keep it open. I would think this would be one of the most well documented Biennales. By making all of the works available to see online generated a sort of conversation. It is a pleasant surprise that so many people including yourself were able to see these artworks. I do believe that the experience online was a positive one.

――Many of the artists in the Biennale were unknown to the art world and some were not even artists. What was the reaction of the art world to the Biennale?

I think they were very excited. It must have been a surprise to encounter artists whom they had never heard of. I think that the word “artist” is a problem because many cultures find that the word “artist” is very restrictive with a single value or idea of art making and it is a very particular kind of identity where I would use the word “creative”. For example, internationally recognised leading scientists also participated in the Biennale and worked with the artists.

Not many people had heard of the Tlingit artist from Alaska, Nicholas Galanin, for instance, including audiences in the USA. However, people were delighted to see his work. His project was very timely given the developments of the BLM movements, and in Australia, ongoing debates and actions around colonial monuments.

Nicholas Galanin, Shadow on the Land, an excavation and bush burial, 2020. Installation view for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Cockatoo Island. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with assistance from the United States Government. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

――The BLM movement has been spreading across the world. The COVID-19 pandemic and the BLM have revealed the present issues we are facing.

Yes,absolutely. It really highlights the issues of boundaries between countries and states and relationships between people. Even though the BLM movement came from the United States of America, like any movement it has huge effects internationally and I also know there are some difficulties even in Japan for those with African-American-Japanese ancestry. Within Australia, “Indigenous Lives Matter” movement is very powerful and supported through the movement of the BLM. There have been over 400 deaths in custody involving Indigenous people in Australia, in the past thirty years. In the Biennale, there were artworks that cast light on such pressing aspects of society and contributed to supporting various social movements in Sydney. The COVID-19 pandemic can both divide and unite people. It has certainly a positive influence on bringing people together.

Australia House

Information

An old minkahouse in Urada area with an approximately 150-year history since the latter half of the Edo period started its new history as a platform to support ongoing exchanges between Australia and Echigo-Tsumari in 2009. However, the house was completely destroyed by the Northern Nagano earthquake in March 2011. An international architecture competition was organised with Ando Tadao leading the jury to build a new house that would be “small, robust and reasonable”. The current Australia House, which is a symbol of the restorationfrom the quake as well as a representation of a future architecture, was chosen from 154 entries and granted the Jørn Utzon award for international architecture in 2013.

The garden designed by Kawaguchi Yutaka / Naito Kaori “The First of the Gardens… then”

Built in 2012

Open during seasonal programs. 10:00 – 16:00 (Closed in winter)

Address: 7577-1 Urada, Tokamachi-city, Niigata, Japan

About the artwork